Equivalent Resistance

Equivalent resistance is the total resistance of a circuit that simplifies multiple resistors into a single resistor. It is calculated differently for series and parallel circuits, helping determine current flow, voltage distribution, and overall power consumption in electrical networks.

What is Equivalent Resistance?

Equivalent resistance is a crucial concept for individuals working with electrical circuits. It:

✅ Represents the single resistance that replaces multiple resistors in a circuit.

✅ Simplifies calculations of current, voltage, and power.

✅ Found using series or parallel formulas based on resistor arrangement.

By mastering the calculation methods for series and parallel circuits, understanding the relationship with Ohm's law, and applying Kirchhoff's laws in more complex situations, you can efficiently analyze and design electrical systems that meet the requirements of various applications. Furthermore, by incorporating equivalent resistance calculations into your skillset, you'll be better prepared to tackle the exciting challenges presented by the ever-evolving world of electronics and power systems.

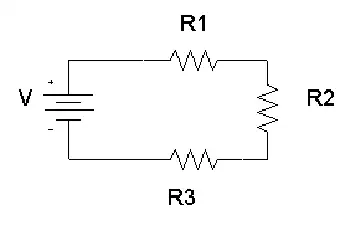

Equivalent Resistance in Series vs. Parallel Circuits

| Configuration | Formula | Key Characteristics | Example Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Series | R_eq = R1 + R2 + R3... | Same current flows through all resistors; total resistance increases; voltage drop varies across components. | For R1=4Ω, R2=6Ω: R_eq = 4Ω + 6Ω = 10Ω |

| Parallel | 1/R_eq = 1/R1 + 1/R2 + 1/R3... | Same voltage across each resistor; total resistance decreases; current divides among paths. | For R1=4Ω, R2=6Ω: 1/R_eq = 1/4 + 1/6 = 0.416 → R_eq ≈ 2.4Ω |

To calculate the equivalent resistance of a network, it is often necessary to determine the sum of the individual resistances. This involves adding the resistance values of each individual resistor in the network, providing a baseline for further calculations. This is a resistance formula for a single resistor, as well as for calculating resistors connected in parallel or in series.

Electrical resistance (R) is a measure of the opposition to the flow of electric current within a circuit. It is determined by the material and dimensions of the conductor, as well as the temperature and other environmental factors. It is measured in ohms (Ω), with lower R indicating greater conductivity and vice versa.

Equivalent Resistance Formula

When a group of resistors is connected end-to-end, they form a series. In a series circuit, the total resistance is equal to the sum of the individual Rs, as current must flow through each resistor in turn. The equivalent resistance of a series circuit is calculated by adding the values of each individual resistor:

Req = R1 + R2 + R3 + ...

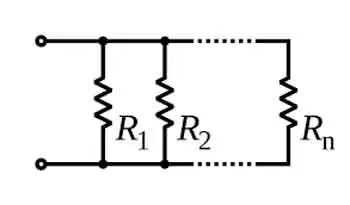

Resistors connected across the same potential difference, or applied voltage, are referred to as being connected in parallel. In a parallel circuit, the total R is less than the R of any individual resistor as the current divides among the resistors. The equivalent resistance of a parallel circuit is calculated using the reciprocal formula:

1/Req = 1/R1 + 1/R2 + 1/R3 + ...

Equivalent resistance is the single R value that can replace a group of resistors in a circuit, offering the same overall R. This simplifies circuit analysis and allows for more straightforward calculations of current and voltage values.

Ohm's law is an essential principle in electronics and relates closely to equivalent resistance. Ohm's law states that the current (I) flowing through a resistor is directly proportional to the applied voltage (V) and inversely proportional to the R. The equation is:

V = IR

By calculating equivalent resistance for a given circuit, we can use Ohm's law to determine the overall current flowing through the circuit and the voltage drops across each resistor.

Series and parallel circuits exhibit different properties when it comes to equivalent resistance. In series circuits, the overall R increases with the addition of more resistors, which means the total current will decrease. In parallel circuits, adding more resistors results in a decrease in total resistance, causing an increase in total current. Understanding these differences is crucial for designing circuits that meet specific electrical requirements.

Kirchhoff's Law

Kirchhoff's laws are another essential tool for calculating equivalent resistance in more complex circuits that cannot be simplified as purely series or parallel. Kirchhoff's current law (KCL) states that the sum of currents entering a junction in a circuit must equal the sum of currents leaving the junction. Kirchhoff's voltage law (KVL) asserts that the sum of the voltages around any closed loop in a circuit must equal zero. By applying these laws, we can create a system of equations to solve for unknown resistance values in a network, ultimately determining the equivalent resistance.

Real-World Applications

Real-world applications of equivalent resistance can be found in various fields, such as electronics, power distribution, and telecommunications. For example, various components have different R values in electronic devices, such as smartphones. Calculating the equivalent resistance enables engineers to design efficient power management systems, ensuring optimal performance and extended battery life. In power distribution networks, equivalent resistance calculations are essential for determining voltage drops and current values across transmission lines, enabling the design of efficient and reliable power delivery systems.

Understanding equivalent resistance is vital for professionals and students who deal with electrical circuits. From simplifying complex networks to designing efficient circuits, equivalent resistance plays a central role in analyzing and developing modern electronic systems. Familiarity with this concept and associated principles like Ohm's law and Kirchhoff's laws ensures a strong foundation for anyone working with electronics, power systems, and telecommunications.

Technology Advances

As technology advances, the importance of equivalent resistance in designing and analyzing new devices and systems will only grow. Calculating and understanding equivalent resistance enables engineers to push the boundaries of innovation and improve upon existing systems, resulting in more efficient, high-performance solutions for consumers and industries alike.

To further develop your understanding of equivalent resistance and related concepts, consider exploring the wealth of educational resources available online and in textbooks, as well as seeking hands-on experience through workshops or real-world projects. Applying this knowledge to practical scenarios will enable you to tackle various electrical and electronic challenges.

Related Articles