Inductive Load Explained

By R.W. Hurst, Editor

An inductive load is common in electrical systems and can significantly impact power quality. Understanding inductive and resistive loads, as well as their impact on the quality of your electricity, is essential for designing and operating an effective electrical system.

What is an Inductive Load?

An inductive load is an electrical device or component that consumes active power while storing energy in a magnetic field due to inductance.

✅ Common in motors, transformers, and relays

✅ Impacts power factor and reactive power demand

✅ Requires compensation with capacitors for efficiency

Power Quality Analysis Training

Request a Free Power Quality Training Quotation

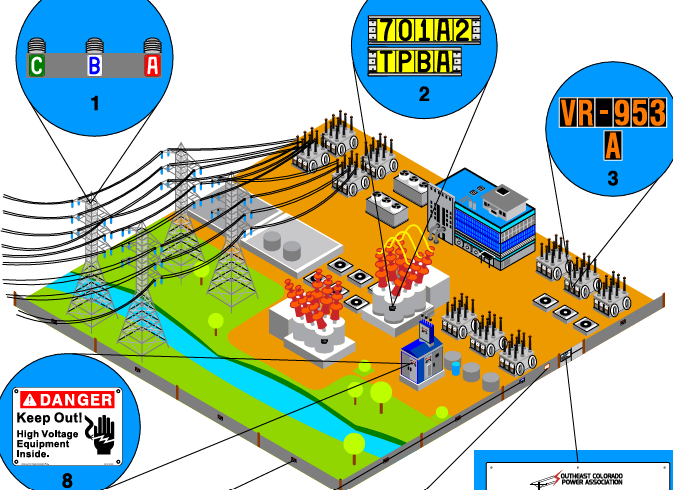

In power systems, an inductive load affects the flow of electrical current through conductors, creating conditions that may necessitate careful monitoring. A hot wire and a neutral wire must be properly balanced to avoid hazards, while ground fault circuit interrupters play a vital role in protecting against dangerous faults. Recognizing early signs of a short circuit, such as tripped breakers or overheating, is essential for maintaining system reliability and preventing equipment damage.

How does it affect Power Quality?

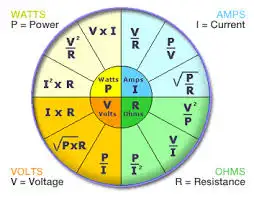

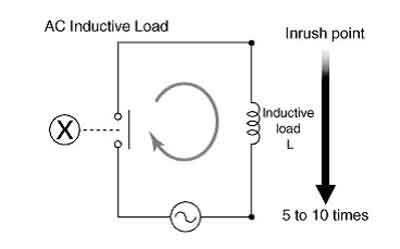

Inductive load affects power quality by introducing reactive power into an electrical system. Reactive power is the power that an IL consumes but does not convert into useful work. This can cause a decrease in the overall PF of the system. A low power factor (PF) can result in increased losses, decreased efficiency, and increased power source costs. Additionally, inductive loads can cause voltage drops and fluctuations, which can affect the operation of other electrical devices. Because inductive devices consume reactive power, engineers often use the apparent power formula to calculate their influence on system demand.

What are the types of inductive load?

There are several types of inductive loads, including electric motors, transformers, and heating elements. Electric motors are used in a wide range of applications, from household appliances to industrial machinery. Transformers are used to step up or step down voltage in electrical systems. Heating elements, such as those used in ovens and stovetops, rely on the inductive heating effect to generate heat. One way to minimize the effect of inductive loads on power factor is by installing an automatic power factor controller.

Common examples include:

-

Electric motors: ILs are commonly found in electric motors used in various appliances, such as washing machines, refrigerators, and air conditioners. Electric motors require electrical energy to create a magnetic field that rotates the motor's shaft, resulting in a lagging current.

-

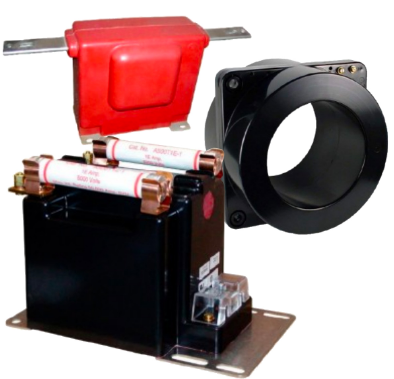

Transformers are devices used to transfer electrical energy from one circuit to another through electromagnetic induction. They are commonly used in distribution systems to step up or step down the voltage to the required level.

-

Fluorescent lights use a ballast to regulate the flow of electricity to the lamp. The ballast contains an IL that helps regulate the electrical current and voltage to the light.

-

Welding equipment: Welding equipment, such as arc welders, use ILs to create a strong magnetic field that is used to generate the heat required for welding.

-

Induction cooktops: Induction cooktops use magnetic fields to create heat, and this requires the use of ILs to generate the magnetic field.

-

Speakers: Speakers use ILs in their voice coils to create a magnetic field that moves the speaker cone and produces sound.

It's essential to understand the different types of electrical load in order to manage consumption and ensure the efficient operation of electrical systems. Different types of loads require different management strategies, and PF correction may be necessary to optimize energy efficiency. Accurate evaluation of an inductive circuit often requires an apparent power calculator to measure kVA, kVAR, and kW contributions.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can you measure the Power Factor of an inductive load?

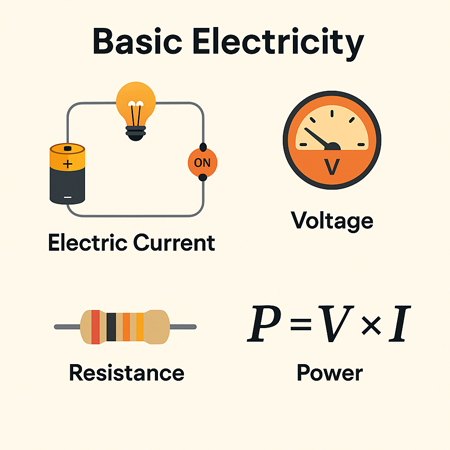

The PF of an IL can be measured using a PF meter or a digital multimeter. These devices measure the PF by comparing the real power (the power that is actually converted into useful work) to the apparent power (the total power consumed by the load). The PF is then calculated as the ratio of the real power to the apparent power. Inductive devices are often compared with a resistive load, which converts all energy into heat or light without reactive power.

What is the difference between a resistive and an inductive load?

A resistive load is a type of electrical load that converts electrical energy into heat or light, such as an incandescent light bulb or a resistor. A resistive load has a PF of 1, meaning that all of the electricity consumed by the load is converted into useful work. In contrast, an IL stores energy in a magnetic field and has a PF of less than 1. This means that some of the electricity consumed by the load is not converted into useful work.

What are some common examples?

Some common examples of ILs include electric motors, transformers, and fluorescent lights. These loads are found in a wide range of applications, from household appliances to industrial machinery.

How can you reduce the impact of inductive load on a system?

There are several ways to reduce the impact of ILs on an electrical system. One way is to improve the PF of the system by adding PF correction capacitors. These capacitors can help offset the reactive electricity consumed by ILs, thereby increasing the PF of the system. Another approach is to utilize soft starters or variable frequency drives with electric motors, which can reduce inrush current and minimize voltage fluctuations. Finally, using a high-efficiency supply or reducing the number of ILs in a system can also help reduce the impact of ILs on PQ. To balance inductive and capacitive elements, engineers apply power factor correction techniques that restore efficiency and reduce system losses.

By understanding the different types, measuring the PF, and reducing its impact on a system, electrical engineers can design and operate systems that are more efficient, reliable, and cost-effective.

It's worth noting that they are not the only types of electrical loads that can impact PQ. Capacitive loads, such as capacitors and fluorescent lights, can also introduce reactive power into a system. Additionally, purely resistive loads, such as resistors and incandescent light bulbs, do not introduce reactive power but can still affect PQ in other ways, including the generation of heat.

Understanding the different types of electrical loads and their impact on PQ is essential for designing and operating efficient and reliable electrical systems. While they can introduce reactive power and affect PF, there are ways to minimize their impact and improve PQ. By taking a holistic approach to electrical system design and operation, engineers can create systems that meet the needs of their users while minimizing costs and maximizing efficiency. Since inductive loads influence reactive currents, using the reactive power formula helps quantify their effect on power system design and operation.

Related Articles