What is Electricity?

Electricity is the flow of electric charge, usually through a conductor like wire. It powers lights, appliances, and machines by converting energy into motion, heat, or light. Electricity can be generated from sources such as fossil fuels, wind, solar, or water.

What is electricity?

Electricity is a fundamental form of energy created by the movement of electrons.

✅ Powers homes, industries, and electronic devices

✅ Flows through circuits as an electric current

✅ Generated from renewable and non-renewable sources

The power we use is a secondary energy source because it is produced by converting primary energy sources such as coal, natural gas, nuclear, solar, and wind energy into electrical power. It is also referred to as an energy carrier, meaning it can be converted into other forms of energy, such as mechanical or thermal energy.

Primary energy sources are either renewable or nonrenewable, but our power is neither.

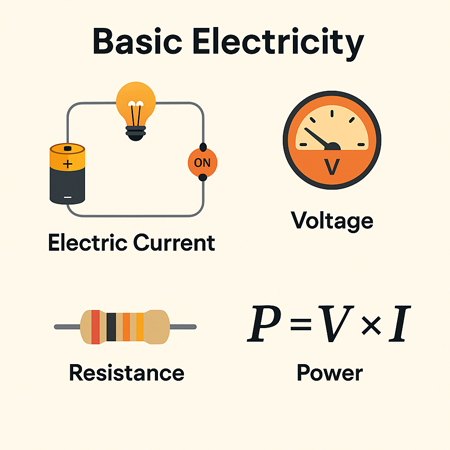

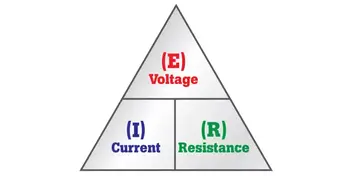

To understand why electrons move in the first place, start with voltage, the electrical “pressure” that pushes charge through every circuit.

Electricity Has Changed Everyday Life

Although most people rarely think about electricity, it has profoundly changed how we live. It is as essential as air or water, yet we tend to take it for granted—until it’s gone. Electricity powers heating and cooling systems, appliances, communications, entertainment, and modern conveniences that past generations never imagined.

Before widespread electrification began just over a century ago, homes were lit with candles or oil lamps, food was cooled with ice blocks, and heating was provided by wood- or coal-burning stoves.

The steady stream of electrons we use daily is explored in our primer on current electricity.

Discovering Electricity: From Curiosity to Power Grid

Scientists and inventors began unlocking the secrets of electricity as early as the 1600s. Over the next few centuries, their discoveries built the foundation for the electric age.

Benjamin Franklin demonstrated that lightning is a form of electricity.

Thomas Edison invented the first commercially viable incandescent light bulb.

Nikola Tesla pioneered the use of alternating current (AC), which enabled the efficient transmission of electricity over long distances. He also experimented with wireless electricity.

Curious why Tesla’s ideas beat Edison’s? Our article on alternating current breaks down the advantages of alternating current (AC) over direct current (DC).

Before Tesla’s innovations, arc lighting used direct current (DC) but was limited to outdoor and short-range applications. His work made it possible for electricity to be transmitted to homes and factories, revolutionizing lighting and industry.

Understanding Electric Charge and Current

Electricity is the movement of electrically charged particles, typically electrons. These particles can move either statically, as in a buildup of charge, or dynamically, as in a flowing current.

All matter is made of atoms, and each atom consists of a nucleus with positively charged protons and neutral neutrons, surrounded by negatively charged electrons. Usually, the number of protons and electrons is balanced. But when that balance is disturbed—when electrons are gained or lost—an electric current is formed as those electrons move.

For a step-by-step walkthrough of everything from circuits to safety, visit how electricity works.

Electricity as a Secondary Energy Source

Electricity doesn’t occur naturally in a usable form. It must be generated by converting other types of energy. In fact, electricity is a manufactured product. That’s why electricity is called a secondary energy source—it carries energy from its original form to where we need it.

We generate electricity by transforming mechanical energy—such as spinning a turbine—into electrical energy. This conversion happens at power plants that use a variety of fuels and methods:

-

Fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas)

-

Nuclear energy

-

Renewable sources like wind, solar, and hydroelectric

If turbines, magnets, and power plants intrigue you, see how electricity is generated for a deeper dive.

How Electricity Was Brought Into Homes

Before electricity generation began on a mass scale, cities often developed near waterfalls, where water wheels powered mills and machines. The leap from mechanical energy to electrical energy enabled power to travel not just across a town, but across entire countries.

Beginning with Franklin’s experiments and followed by Edison’s breakthrough with indoor electric light, the practical uses of electricity expanded rapidly. Tesla’s AC power system made widespread electric distribution feasible, bringing light, heat, and industry to homes and cities worldwide.

How Transformers Changed Everything

To transmit electricity efficiently over long distances, George Westinghouse developed the transformer. This device adjusts the voltage of electrical power to match its purpose—high for long-range travel, low for safe use in homes.

Transformers made it possible to supply electricity to homes and businesses far from power plants. The electric grid became a coordinated system of generation, transmission, distribution, and regulation.

Even today, most of us rarely consider the complexity behind our wall sockets. But behind every outlet lies a vast infrastructure keeping electricity flowing safely and reliably.

How Is Electricity Generated?

Electric generators convert mechanical energy into electricity using the principles of magnetism. When a conductor—such as a coil of wire—moves through a magnetic field, an electric current is induced.

In large power stations, turbines spin magnets inside massive generators. These turbines are driven by steam, water, or wind. The rotating magnet induces small currents in the coils of wire, which combine into a single continuous flow of electric power.

Discover the principle that turns motion into power in electromagnetic induction, the heart of every modern generator.

Measuring Electricity

Electricity is measured in precise units. The amount of power being used or generated is expressed in watts (W), named after inventor James Watt.

-

One watt is a small unit of power; 1,000 watts equal one kilowatt (kW).

-

Energy use over time is measured in kilowatt-hours (kWh).

-

A 100-watt bulb burning for 10 hours uses 1 kWh of electricity.

These units are what you see on your electric bill. They represent how much electricity you’ve consumed over time—and how much you’ll pay.

When it’s time to decode your energy bill, the chart in electrical units makes watts, volts, and amps clear.

Related Articles