Hydroelectricity Explained

Hydroelectricity converts hydropower into grid-ready electricity using dams, penstocks, turbines, and generators, enabling renewable baseload, pumped storage, high efficiency, and low emissions for resilient power systems with load balancing, frequency regulation, and strong capacity factors.

What Is Hydroelectricity?

Hydroelectricity is electricity generated by water turning turbines at dams, delivering low-carbon power to the grid.

✅ Converts hydraulic head and flow into alternating current.

✅ Uses synchronous generators, excitation, and step-up transformers.

✅ Supports grid inertia, regulation, and pumped-storage balancing.

Hydroelectricity is another term for power generated by harnessing the power of damming rivers and moving water into generating plants. Not necessarily falling water, just moving water. There are many famous such Hydroelectricity stations in the world, not the least of them at Niagara Falls, Grand Coulee and Boulder Dam and the three gorges dam in China . In the past, small plants produced electric hydroelectricity. Now, they are massive in size and generation capcity as well as having large reservoirs. If there is a need for power electrical generation stations situated close to the point of consumption is ideal. These are just a few of the many examples of energy produced by falling water. On the other hand, a small mill set in the rapids of a fast-moving stream is also an example of it in action, on a lesser scale. The truth is that any steady current of flowing water from a river or other waterway can be converted to power. Of all the sources electricity from hydroelectricity, dammed reservoirs is one of the cleanest possibe ways to generate electricity to a million people, compared with nuclear power. For broader background on water safety and power concepts, the guide on water and electricity explains interactions, risks, and basic generation principles.

How is HydroElectricity Generated?

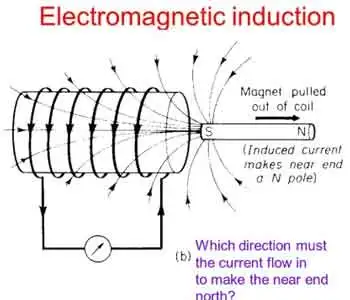

Hydroelectricity is generated or "manufactured" in large hydroelectric plants, (electrical generating stations) using the same basic principle as a small grist mill yet on a much larger and vastly improved scale for better efficiency, using pumped storage. These power plants contain electrical generators which are attached to massive turbine devices which spin at great speeds as a result of water rushing through them. These pump water power station turbines are much more efficient at extracting the kinetic energy from the moving water and converting that energy it into electrical production through these generators. To see how hydro fits within the wider energy landscape, review how electricity is generated across different prime movers and grid systems.

The amount of electricity from Hydroelectricity extracted from water as an energy source depends not only on the capacities of volume sent through a hydroelectric power plant but on the difference in height between the source and the water's outflow. This height difference is called the head. The amount of potential energy in water is directly proportional to the head and how much water is released. To obtain very high head, water for a hydraulic turbine may be run through a large pipe called a penstock. These relationships between flow, head, and output are core electricity generation principles that guide plant design and optimization.

For instance, energy is derived to make electricity water has to move from a higher elevation to a lower elevation through a large tube" otherwise known in technical terms as a "penstock". When the water reaches the end of the penstock, it turns a water wheel or "turbine" at enormous speeds. The turbine rotates, via a connected shaft to an electrical generator, and this generator creates electricity. It is the turbine and generator working in combination that converts "mechanical energy" into "electric energy". The water that makes this possible, is a renewable energy resource, just like the wind that turns the turbine attached to a generator. This mechanical-to-electrical conversion is a classic way to generate electricity efficiently when hydraulic conditions are favorable.

Hydroelectricity may be extracted from water but it depends not only on the volume of water but also on the difference in height between the top of the penstock and where the water spins the turbine. This difference in height is often referred to as the "head". From this "head", it can be determined the exact amount of potential energy that can be converted. Therefore, it is advantageous to build power dams as high as possible to convert the maximum energy from mechanical energy. Project planners evaluate head, flow duration, and dispatch needs in the context of overall electricity production targets and grid reliability.

While many hydroelectricity generating stations supply world power grids, some projects are created for private business purposes. For example, aluminium manufacturing companies require large amounts of power. And there are many other examples of industries that use hydroelectricity in their manufacturing operations. Industrial facilities often diversify procurement among various sources of electricity to balance costs, resilience, and sustainability goals.

While hydroelectricity in the United States seems relatively clean and safe in comparison to burning fossil fuels (coal or oil or natural gas), nearly all large hydroelectricity installations in North America have significant had impacts on nearby environmental habitats once they are brought online. This is because they significantly impede the flow of water in rivers and lakes at the point where the generating dam is installed In turn, this causes significant increases in water levels in corresponding upstream water systems while at the same time creating much lower water levels downstream. Mitigation strategies may include fish passages, adaptive flow management, and complementary alternative electricity options to reduce ecological disruption.

_1497174879.webp)