Wireless Electricity

Wireless electricity transmits power without wires using electromagnetic fields, such as magnetic resonance or microwave transmission. It enables charging devices remotely, powering sensors, and improving efficiency in smart grids, EVs, and wireless charging systems.

What is Wireless Electricity?

Wireless electricity refers to the transmission of electrical energy without physical conductors like wires.

✅ Powers devices through electromagnetic fields, like inductive coupling

✅ Enables contactless charging in consumer electronics and EVs

✅ Supports smart grids, IoT, and remote sensors with flexible energy delivery

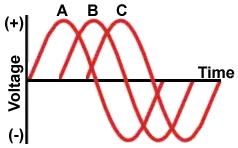

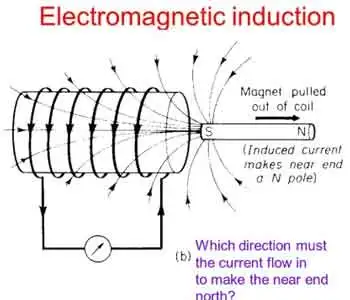

Wireless electricity, also known as wireless power transmission, was first conceptualized by Nikola Tesla, a pioneer in the field of alternating current (AC) electricity. Tesla’s groundbreaking experiments at Colorado Springs in 1899 showcased how power could be transmitted without wires using a magnetic field. He used a Tesla coil to transmit 100 million volts of high power over a distance of 26 miles, wirelessly powering 200 light bulbs and an electric motor. His vision was to develop a wireless system capable of transmitting power over long distances with minimal energy loss.

Tesla’s system relied on a high-frequency alternating current and magnetic resonance to transmit power wirelessly. His experiments with the Tesla coil laid the groundwork for modern wireless technologies, including short-range wi

reless power transmission systems, such as wireless charging pads and Wi-Fi routers. Wireless charging pads today utilize magnetic fields to transmit power to devices, a concept similar to Tesla’s idea of harnessing the Earth’s resonance to transmit power over longer distances. Tesla’s vision extended beyond short-range wireless systems—he dreamed of a global system where energy flows freely through the air without requiring a direct line of sight.

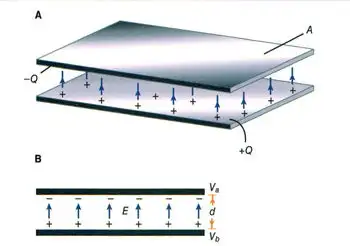

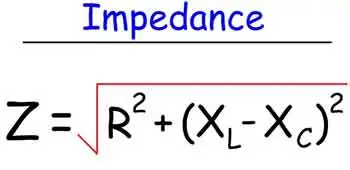

Tesla’s experiments also demonstrated the efficiency of wireless systems. The Tesla coil could transmit power wirelessly to fluorescent light bulbs even when they were several feet away from the coil. This concept of powering devices wirelessly has evolved over time, with companies like Wi-Charge developing systems to transmit power wirelessly to small devices. In Tesla’s time, he envisioned a world where any amount of power could be transmitted wirelessly across the globe. However, financial struggles eventually led to the abandonment of his wireless power transmission projects, including the unfinished Wardenclyffe tower on Long Island. Devices powered wirelessly still rely on efficient energy flow, making concepts such as electrical resistance and impedance crucial to design and performance.

Despite Tesla’s challenges, modern advancements have kept his vision alive. Short-range wireless power transmission systems, like those used in Wi-Fi routers and wireless charging pads, are now commonplace. These technologies utilize magnetic fields to transmit power wirelessly over short distances, offering a practical solution for wirelessly charging devices such as smartphones and laptops. Wi-Charge is exploring the potential of wirelessly charging devices without requiring close contact, enabling more flexible and efficient energy distribution. Tesla’s coil and modern systems like Wi-Charge operate based on resonant principles, closely related to inductance and capacitance.

Modern Innovations in Wireless Electricity

Recent breakthroughs have brought Tesla’s dream closer to reality:

-

In 2024, DARPA successfully transmitted 800 watts of power over 5 miles using a laser beam—enough to make popcorn at the receiver site.

-

KAIST in South Korea demonstrated the ability to charge 40 smartphones at once using magnetic resonance over a distance of 5 meters.

-

Detroit’s Corktown district now hosts a functioning inductive charging roadway, allowing EVs to charge wirelessly while in motion.

These examples show that wireless electricity is no longer a distant vision but a rapidly advancing technology with real-world applications. Concepts such as watts, volts, and amperes remain fundamental even in advanced wireless systems.

Types of Wireless Power Transmission Technologies

| Technology Type | Description and Use Cases |

|---|---|

| Inductive Coupling | Short-range charging pads for phones, laptops, and wearables |

| Magnetic Resonance | Mid-range charging for larger devices and multiple receivers simultaneously |

| Microwave Transmission | Long-range point-to-point energy transfer; used in research and satellites |

| Laser Power Beaming | High-efficiency focused beams for distant targets; demonstrated by DARPA |

| Infrared Light (Wi-Charge) | Contactless charging for smart locks and IoT devices |

Applications of Wireless Electricity

-

Consumer Electronics: Wireless charging pads and smart home devices are now common.

-

Electric Vehicles (EVs): Inductive charging roads and parking pads reduce dependency on cable stations.

-

Medical Implants: Enables powering of implants and biosensors without invasive wiring.

-

Remote Sensors: In agriculture, factories, and infrastructure, wireless power extends sensor life.

-

Smart Grids: Flexible energy distribution for remote locations and emergency response.

Challenges and Future Outlook

Despite its promise, wireless electricity faces challenges:

-

Efficiency drops over distance

-

Alignment issues in inductive systems

-

Line-of-sight limitations in laser and IR systems

-

Safety regulations for high-power beaming

However, the future is promising. Emerging materials, such as metamaterials and metasurfaces, are enhancing transmission efficiency. AI-enhanced beam control, dynamic alignment systems, and frequency-agnostic receivers are under development.

From Tesla's early experiments to DARPA's record-setting laser transmission, wireless electricity is evolving into a transformative force. As the technology matures, its applications will expand, powering a world that may one day be truly wire-free.

Related Articles