What is Distributed Generation? Explained

By Harold WIlliams, Associate Editor

Distributed generation refers to the local production of electricity using renewable energy, microgrids, and small-scale systems. It enhances efficiency, minimizes transmission losses, and facilitates reliable and sustainable power distribution in modern electrical networks.

What is Distributed Generation?

It involves the decentralized production of electricity near consumers, utilizing renewable energy sources, combined heat and power systems, and microgrid technologies.

✅ Provides local electricity generation near demand points

✅ Improves grid reliability, energy efficiency, and sustainability

✅ Reduces transmission losses and supports renewable integration

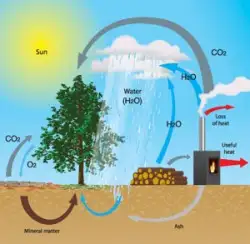

What is distributed generation? Distributed generation systems are transforming how communities generate electricity by shifting away from exclusive reliance on traditional centralized power plants. These systems often combine renewable sources with local energy solutions, and in some cases use natural gas for backup or combined heat and power applications. By operating closer to the point of use, distributed generation reduces transmission losses, supports energy efficiency, and decreases dependence on fossil fuels, helping to build a more sustainable and resilient power network.

Distributed Generation Training

How Distributed Generation Works

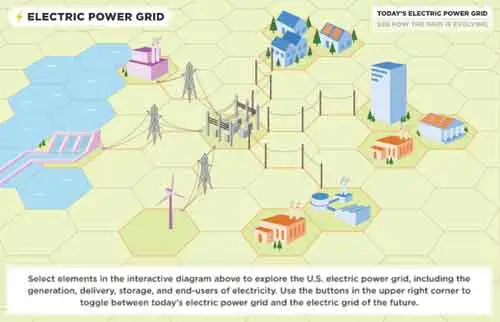

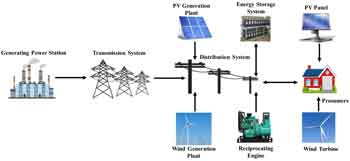

Distributed generation functions through on-site or near-site production of power. While centralized generation transmits electricity across hundreds of miles, DG creates it close to consumption, reducing energy losses and infrastructure needs. The process begins with various small-scale technologies, each designed to serve specific needs. Some systems connect directly to the larger utility grid, while others operate independently within microgrids. Energy storage plays a vital role, allowing surplus power to be stored and released during periods of peak demand, thereby improving energy resilience and grid balance.

Key technologies include:

-

Solar photovoltaic (PV) panels, widely deployed in residential rooftops and utility microgrids, convert sunlight into electricity.

-

Wind turbines, both small-scale and community-based, deliver renewable power directly to local users.

-

Fuel cells generate clean, reliable electricity through chemical reactions, making them ideal for critical infrastructure.

-

Combined heat and power (CHP) systems capture waste heat during electricity generation to improve total efficiency.

-

Microgrids integrate multiple DERs and can disconnect (“island”) from the main grid during outages to supply continuous power.

-

Energy storage systems, such as batteries, provide flexibility, backup supply, and peak demand management capabilities.

Benefits of Distributed Generation

The benefits of DG extend well beyond simple power supply. At its core, DG enhances the overall performance of electrical systems by placing power sources closer to demand, thereby reducing reliance on long-distance transmission and minimizing losses. It supports the transition to cleaner energy by enabling the integration of renewable sources, strengthens resilience by diversifying power sources, and reduces stress on centralized grids during peak demand. Communities, businesses, and utilities alike benefit from increased security, sustainability, and cost savings when they adopt DG.

DG delivers multiple advantages:

-

Higher energy efficiency, as CHP systems and other technologies recover waste heat for practical use.

-

Reduced transmission losses, since electricity does not need to travel across extensive networks.

-

Grid reliability and resilience, with local systems ensuring power supply even when centralized networks fail.

-

Renewable integration provides a pathway for solar, wind, and other sustainable technologies.

-

Peak demand management helps balance the electricity supply during periods of high consumption.

-

Energy independence is particularly important for remote or underserved communities that cannot rely on centralized grids.

Regulatory Standards and Policies

The adoption of DG depends heavily on regulatory frameworks that govern safety, interconnection, and compensation. Technical standards, such as IEEE 1547, define the rules for how distributed energy resources connect to the grid, addressing voltage regulation, protection coordination, and power quality. Without clear standards, widespread deployment would risk instability and safety issues.

Government policies also provide critical support. Net metering programs enable households and businesses to sell excess electricity back to the grid, making the adoption of renewable energy more affordable. Feed-in tariffs create financial incentives for producers by guaranteeing payment for electricity generated from renewable sources. Grid interconnection standards ensure that systems connect seamlessly without harming existing infrastructure. Together, these regulations provide structure, encourage investment, and shape the growth of distributed generation worldwide.

Challenges of Distributed Generation

While DG offers many advantages, it also introduces challenges that must be addressed for long-term success. The most obvious barrier is financial: new systems require significant investment in generation capacity, storage, and interconnection. Technical issues, such as managing voltage fluctuations, maintaining power quality, and integrating many small systems into a stable grid, also create complexity. As adoption grows, utilities must develop smarter monitoring and control systems to coordinate multiple inputs. Ultimately, regulatory uncertainty in certain regions can deter investment.

Key challenges include:

-

High initial investment costs limit adoption, despite the potential for long-term savings.

-

Grid management issues arise with the increasing number of decentralized resources, complicating system operations.

-

Power quality and control concerns require advanced technologies to maintain stability.

-

Regulatory hurdles, as inconsistent policies, can slow or prevent project development.

Real-World Examples

Distributed generation is already reshaping global energy systems:

-

United States: California leads the way with extensive rooftop solar adoption, supported by net metering policies and community microgrids that supply critical facilities during power outages.

-

Germany: Its feed-in tariff system has transformed the energy landscape by encouraging the integration of distributed solar PV and wind, making it a world leader in renewable energy adoption.

-

Canada: Remote northern and Indigenous communities are turning to DG solutions, which combine solar panels, battery storage, and backup generators, to reduce their reliance on diesel and improve reliability.

-

India: Solar microgrids are expanding electricity access to rural villages, providing sustainable power where centralized infrastructure is impractical.

These examples illustrate how DG provides environmental benefits, cost savings, and enhanced energy resilience across diverse regions.

Future Trends in Distributed Generation

The future of Distributed Generation lies in smarter, more integrated energy systems. As renewable energy continues to grow, distributed generation will play a central role in balancing demand and supply at the local level. New technologies, such as battery storage systems and smart inverters, are making grids more adaptable. Peer-to-peer energy trading platforms are emerging, allowing consumers to buy and sell electricity within communities. Virtual power plants (VPPs), which aggregate thousands of small resources into coordinated grid assets, will enhance efficiency and resilience. Looking further ahead, hydrogen fuel cells and hybrid renewable systems will expand the reach of DG into industrial and transportation sectors.

Emerging trends include:

-

Battery storage for greater flexibility and backup.

-

Smart inverters that maintain stability during variable renewable generation.

-

Peer-to-peer trading, enabling community-level energy exchange.

-

Virtual power plants (VPPs) that combine DERs into large, coordinated resources.

-

Hydrogen technologies offer clean and scalable options for generating energy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between distributed generation and dispersed generation?

Although often used interchangeably, dispersed generation usually refers to small-scale power produced in isolated locations away from the grid, while distributed generation emphasizes systems located close to consumers, often integrated with microgrids.

What is distributed generation, and what are the pros and cons?

Pros include increased efficiency, renewable energy integration, improved grid resilience, and reduced transmission losses. Cons involve high infrastructure costs, regulatory complexity, and grid management challenges.

What is the difference between distributed generation and a microgrid?

A microgrid is a self-contained energy network that can operate independently. Distributed generation refers to the small-scale power sources—such as solar panels or CHP systems—that may be part of a microgrid.

What are examples of distributed generation technologies?

Examples include solar PV, wind turbines, CHP systems, fuel cells, energy storage, and integrated microgrids.

What role do regulations play in distributed generation?

Standards like IEEE 1547, along with policies such as net metering and feed-in tariffs, govern the safe interconnection of Distributed Generation and provide financial incentives that support its wider adoption.

How can distributed generation improve grid resiliency?

By diversifying energy sources and enabling localized supply, DG ensures backup power for critical facilities during outages and reduces the impact of large-scale disruptions.

What is Distributed Generation? Distributed generation represents a shift from traditional centralized power plants to localized, flexible energy solutions. By integrating renewable resources, natural gas, and advanced technologies like microgrids and storage, DG improves efficiency, reduces reliance on fossil fuels, and enhances grid resilience. As policies, standards, and innovations continue to evolve, distributed generation will play an increasingly vital role in building a sustainable, reliable, and future-ready energy system.

Related Articles

_1497100159.webp)